Thomas Hodges

- Date of Brass:

- c. 1630

- Place:

- Wedmore

- County:

- Somerset

- Country:

- Number:

- I

- Style:

- Edward Marshall

Description

December 2018

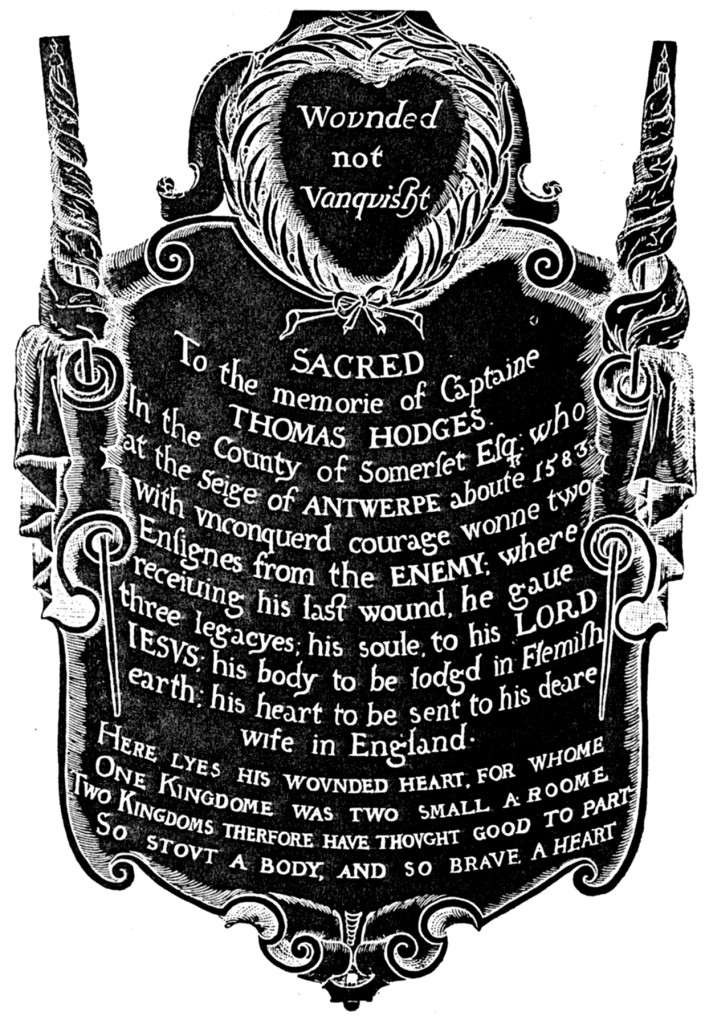

This month’s contribution is a rare example of a heart monument in brass, the tribute of his devoted wife, Agatha. Brass heart monuments are extremely unusual, although more survive carved in stone. They take many iconographic forms, the most common being a mural canopied niche with some form of heart imagery within. The example at Wedmore is mounted on the north wall of the north aisle. It comprises an elaborate scroll bearing the inscription topped by a heart surrounded by a wreath of bay with the motto ‘Wounded not Vanquished’ and flanked by two ensigns. The inscription reads: SACRED to the memorie of Captaine THOMAS HODGES In the County of Somerset Esq. who at the seige of ANTWERPE about 1583 with vnconquerd courage wonne two Ensignes from the ENEMY where reciuing his last wound he gaue three lagacyes, his soul to his Lord Iesvs, his body to be lodged in Flemish earth, his heart to be sent to his deare wife in England. HERE LYES HIS WOVNDED HEART, FOR WHOME ONE KINGDOME WAS TWO [SIC] SMALL A ROOME TWO KINGDOMS THEREFORE HAVE THOUGHT GOOD TO PART SO STOVT A BODY AND SO BRAVE A HEART’.

Captain Thomas Hedges was the son of Thomas Hedges the elder of Wedmore (d. 1600) and his wife Margaret (d. 1617) He married Agatha, daughter of George Rodney of Westbury (Wiltshire). They had one son, George (d. 1634). Thomas Hedges the elder requested in his will to be buried ‘in the north Ile of Wedmere church’ although no monument survives. George was also buried there and is memorialised by a figure brass near that of his father. The inscription records that he was interred ‘in the sepuvlcher of his grandfather and father’.

There are various reasons why divided burial, with separate interment of the heart and sometimes also the viscera, took place. First was the example of those who died abroad in the crusades and other wars choosing to send back their hearts to a family foundation. A second possible factor could have been romantic attachment. Both these explanations apply in this case.

The theological arguments over divided burial provide a key context for the lay attitude to the practice over time, explaining why heart burials were more common in some periods than others. For many years theologians’ views were based on the teachings of St Augustine of Hippo (d. 430). He argued that the fate of corporeal remains was meaningless to the dead themselves and that Christians should not be concerned about burial, since they had been promised reintegration of the body, wherever the parts had been dispersed. This led many to accept division of the body for burial in multiple locations as consistent with Christian teaching. However, the position evolved until Boniface VIII, pope from 1294 to 1303, specifically in his bull Detestande feritatis, first issued in 1299 and reissued the following year, condemned in vitriolic terms separation of the parts of the body. After Boniface’s death there was a gradual relaxation in the prohibition of divided burial.

Amongst the earliest English people whose corpses received this treatment were: William Giffard, bishop of Winchester and Chancellor of England (d.1129), whose heart was found when a wall at Waveley Abbey (Surrey) was taken down, revealing a stone depository with two leaden dishes soldered together; Edith, wife of Robert D’Oiley, (d.1127), whose heart was interred in Osney Abbey, Oxford, and who was memorialised by a lost effigy showing her as a vowess holding a heart; and Stephen, earl of Brittany and Richmond (d. 1138), whose heart was buried in the priory of St Martin, Richmond, a now largely destroyed cell of St Mary’s Abbey, York. The majority date before 1299, but they can be found much later, for example the poet and novelist Thomas Hardy (d.1928).

Sally Badham

- © Monumental Brass Society (MBS) 2026

- Registered Charity No. 214336