Conservation

A prime objective of the Monumental Brass Society is to ensure the better preservation of monumental brasses, indents of lost brasses and incised slabs. The Society provides advice and assistance to churches on the care and preservation of their brasses. It also has a Conservation Fund, from which grants are provided to churches for conservation work on brasses.

If you would like to go direct to a particular section, click on the section headings below:

- Guidance to churches on the care and conservation of brasses and slabs

- Conservation methods

- MBS Conservation Fund

- Guidance for grant applications

Guidance to churches on the care and conservation of brasses and slabs

The following advice is offered to parishes by the M.B.S. through the good offices of the Church Buildings Council

and local Diocesan Advisory Committees (D.A.C.s).

Underlying the specific advice below are two essential musts -that expert advice on conservation of your brasses and slabs must be sought through your D.A.C. and you must steer clear of using the local jobbing builder or enthusiastic amateur.

If your brasses are in need of attention now or in the future, financial help is readily available. The M.B.S. provides small grants and there are various other charitable bodies that will provide funds for the conservation of brasses, slabs and larger monuments but only if authorised expert conservators are employed; your local D.A.C. Secretary can supply you with details.

Protection from theft

- If a brass becomes loose, or proud of its slab, it should be reported to the Diocesan Advisory Committee; if any part, however small, is completely loose it should immediately be removed to a safe place.

- Brasses removed from their slab and wall mounted should be secured to a board of chemically-inert wood (oak is unsuitable) by rivets.

Protection from damage

- Brass rubbing does not harm a brass if competently carried out, and the brass is securely fixed. Rubbers should be discouraged from kneeling or resting on brasses while working and should always use kneelers. Sticky tape must not be applied to the brass or its slab, though dry masking tape is permissible. If a brass is frequently rubbed then the church should consider having a replica made for the purpose. The rubbing of brasses that are not securely fixed and firmly supported at the back should be prohibited until they have been attended to by a conservator, since applied pressure causes the metal to flex and may result in cracking or other damage.

- People should be prevented from walking or kneeling directly on brasses and incised slabs. This can be achieved either by roping off the monuments or covering them with a layer of soft chemically-inert felt under a woven carpet.

- Under no circumstances should coconut-matting or rubber, plastic or foam backed carpets be used to cover brasses or slabs since all cause serious damage to anything underneath them (impermeably-backed carpets can also cause serious damage to the fabric of the church by driving damp up the walls). Coconut or other coarse matting trap grit and dirt which will abrade the surface of the brass or slab, while (rubber) backed carpets can produce corrosion by trapping moisture or giving off harmful chemicals as they deteriorate. If a fixed carpeting scheme is being considered which is likely to cover brasses and slabs on a fairly permanent basis then please seek advice on the type of carpet and underlay to be used and consider having inspection panels in the carpet so that the brasses may be viewed and their condition monitored.

- Brasses and incised slabs should not have candlesticks, vases or furniture placed on them; chair legs can scratch and loosen the brass and damage the stone. Avoid putting floral displays on brasses as spillage causes damp and corrosion.

- Brasses in slabs, on tomb chests or on wall monuments, and also incised slabs will suffer if the monument is affected by damp. Damp is particularly damaging to Purbeck marble and other shelly limestones. Danger signs are: crumbling powdery stone surface, flaking paint, water marks or green stains or salts on the stonework, brown stains on wall monuments or tomb chests, or cracks in the stonework. Slabs affected by damp should, wherever possible, be left uncovered. Expert advice must be sought on how to isolate the monument from the source of the damp, how to repair any damage and make the monument safe. Brass rubbing should be prohibited if the slab is showing signs of damp problems as it may hasten the deterioration.

- Brasses should never be cleaned using metal polishes or other chemical cleaners. These contain abrasives, and/or acids, which can quickly remove the engraving. Usually brasses only require dusting. Any blue or green corrosion should only be removed by a trained conservator.

- Brasses screwed to lime washed walls, or in contact with lime based plaster or cement, are likely to be suffering unseen corrosion on the back; instead have the brass mounted on a board of chemically-inert wood (not oak as it is unsuitable) which can itself be fixed to the wall. A small air gap should be left to prevent a build up of condensation.

- During interior decoration, monuments, including brasses, should be properly covered to protect them. Also if your church has a colony of (protected) bats the corrosive effects of their droppings on brasses can be severe so brasses and slabs should be covered to prevent damage. Historic England and Natural England have produced useful guidelines for the identification, assessment and management of bat-related damage to church contents.

The above advice is, of necessity, a brief summary. For expert advice on the care of brasses and slabs please contact your local D.A.C. who can put you in touch with your local consultant, if you have one, or contact:

Martin Stuchfield

Hon. Conservation Officer

Pentlow Hall

Cavendish

Suffolk CO10 7SP

conservation@brasses.org

Conservation methods

This article first appeared in The Conservation and Repair of Ecclesiastical Buildings (The Building Conservation Directory Special Report...No 1, Third Edition Summer 1996) and subsequently in the Conservation Special issue of Bulletin 75 (June 1997). It is reproduced by the kind agreement of the author, William Lack.

The earliest brasses were laid down in this country in the early 14th century and their popularity as memorials for the landed gentry and wealthy middle classes continued until the mid 17th century. Iconoclasm, greed and carelessness have reduced the original number of brasses to a current total of about 8,000. Many of these are to be found in comparatively isolated churches throughout the country with a concentration in the home counties and East Anglia. A brief revival in Victorian times produced a fair number of notable examples and a few brasses have been laid down up to the present day.

The greatest danger facing brasses is theft. Therefore the first priority of the conservator is to ensure that the brasses are secure, either in their original slabs or in an alternative setting.

Every brass was originally set in a stone slab, often of Purbeck marble, which was itself an integral part of the monument. The brass was secured with brass rivets set in lead plugs let into the stone and the plates were bedded on pitch. Over a prolonged period pitch deteriorates and loses its adhesion, rivets spring or pull out of the stone, and the endless pressure of feet causes plates to expand laterally and to bow. As a result, plates work proud of their slabs and become loose and vulnerable. Brasses which have been reset in their slabs in the past using screws or other inappropriate techniques are particularly vulnerable. When set in the floor of a church, corrosion is not usually a problem unless the brass has been re-laid and bedded unsuitably, for example on cement.

The conservator's first task is to clean the plates, taking care not to disturb the existing patina. It is most important that this is done without the use of chemicals. After light washing in distilled water or white spirit, dirt, corrosion and calcareous accretions are carefully scraped off and lifted with a scalpel. New brass rivets are fitted and the brass secured in its original slab with the plates bedded on fresh bituminous mastic with the rivets set in an inert resin grout. This process, which follows the original methods, provides support and secure anchoring for the brass and protection from damp.

On church floors slabs have usually survived remarkably well. However, problems which are encountered include fracturing of the stone and deterioration of the surface, either caused by heavy foot traffic or by environmental conditions where rising damp and migrating salts have caused crumbling of the stone surface, often leaving edges of plates exposed.

Wherever possible, a damaged slab should be conserved by a stone conservator. It may need to be removed from the floor, dried out and the level of soluble salts reduced by expert treatment. Any fractures will need to be pinned with stainless steel dowels and the surface may need to be consolidated. Limestones and calcareous sandstones may be consolidated using limewater but not an impervious chemical, as most proprietary treatments are liable to lead to further deterioration and cannot be reversed. In extreme cases the surface may need to be dressed and new indents cut.

The Victorian fashion for tiling church floors resulted in the loss of many original stone slab floors. Brasses were often removed to the walls where they may now be found nailed or screwed directly to damp, plastered and lime-washed walls. Not only are such brasses more vulnerable to theft but they have usually become corroded. It is common to see green (copper carbonate) corrosion round the edges of the plates and ferrous corrosion round the fixings.

Where corrosion has occurred, the brass must be removed from the source of damp and cleaned. If the original slab cannot be reused, or if replacing it in its original position would entail unacceptable risk of further deterioration, a cost-effective solution is to mount the brass on a board. Whilst this may not be an ideal solution from an aesthetic or historic viewpoint, it nevertheless provides better security and protection against corrosion and wear, provided the brass is properly rebated and riveted to the board. The board should be spaced away from the wall to allow air circulation behind and should be secured with stainless steel anchor bolts. The wood should be stable and free from natural chemicals which may react adversely with the brass. For this reason oak, Douglas fir and certain other hardwoods are not suitable. Iroko, beech and cedar of Lebanon are among those currently in use although each has its disadvantages.

Victorian plates present unique problems. Many of them were secured with rivets soldered to the reverse and these joints can fail, leaving edges proud of the slab. In such cases it is usually necessary to lift and conserve the whole plate. These brasses were produced with coloured infill in the engraved lines and their surfaces were polished and protected with lacquer. Where the lacquer has broken down, either as a result of polishing or environmental conditions, the brass will need to be cleaned, lightly polished and re-lacquered with a cellulose lacquer such as Incralac.

In the 1960s and 1970s brass rubbing achieved great popularity and many celebrated brasses were rubbed intensively. Brass rubbing was perceived to damage brasses, and a by-product of the brass rubbing boom was the emergence of resin facsimiles. In churches where brass rubbing is most popular, facsimiles can be introduced to ensure the protection of the originals. Although excessive rubbing almost certainly contributed to a loosening of some brasses and caused damage where plates were not securely fixed and could be flexed vertically, recent study 'Wear of English Monumental Brasses caused by Brass Rubbing', by J.T. Yates, T.E. Madey and H.L. Rook, Nature, 243 (1973), pp.422-4) has shown that brass rubbing, if properly carried out, does not wear the surface.

Most damage has been caused by the use of metal polish and by injudicious use of coverings such as coconut matting and carpets with underlay which harbour grit. The practice of laying fitted carpets with rubber underlay prevents floors and slabs from breathing and inevitably causes corrosion to brasses, while any grit caught beneath abrades the surface.

Some medieval brasses were made by reusing older ones, and lifting of brasses for conservation has revealed many unknown 'palimpsests', with the older engravings preserved on the reverse side. After conservation, the reverse will again be concealed so they should be recorded by taking a rubbing or by making a resin facsimile for display elsewhere in the church.

Where brasses have been conserved, the only action necessary to maintain them is to ensure that they are kept regularly swept with a soft brush and protected with regular applications of micro-crystalline wax.

Back to the top

MBS Conservation Fund

During the early years of the Society there was little focused or reported activity of the repair and restoration of brasses. The dissolution of the Society at the onset of war in 1914 precluded any organised encouragement of conservation, but its

re-founding in 1934 provided an opportunity for one of the rules clearly to state that the Society should endeavour 'to ensure the better preservation of brasses and slabs'.

In 1973 the then President of the M.B.S., Dr. Cameron, a metallurgist in the University of Cambridge set up a specialised laboratory for the repair of brasses. A separate fund to support this work was established by the M.B.S., primed by grants and later supported by donations, specific fund-raising events and bank interest. With the death of Dr. Cameron in 1985 the tangible link of the Society with Cambridge was lost; since then the Society has not been involved in the practical aspects of conservation work. Recognising this the Laboratory/Workshop account was renamed the 'Monumental Brass Society Conservation Fund' from which grants are awarded to churches on application.

Back to the topGuidance for grant applications

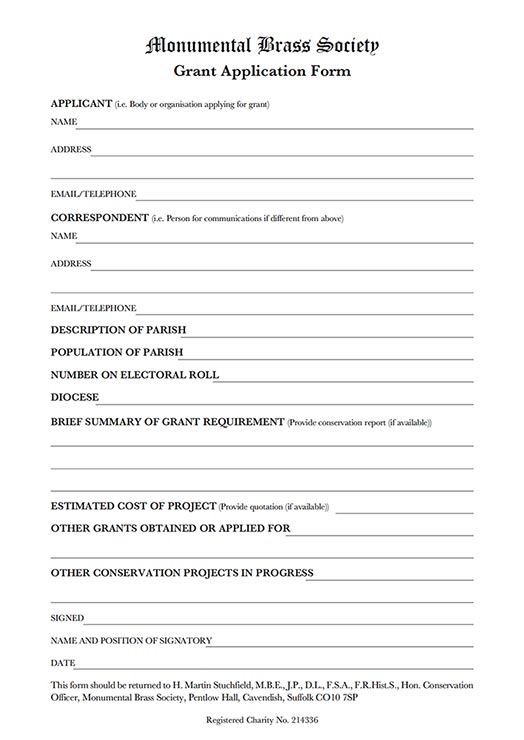

The M.B.S. Conservation Fund has limited resources and is usually able to make grants totalling around £600 to £800 each year. The policy is to spread this sum as far as possible, striving to ensure that most, if not all, applications receive a grant, however small. Most individual grants are usually in the range £50 to £200. However, as a primary fund the M.B.S. Conservation Fund frequently opens the door to larger, less publicised resources.

To apply for a grant from the Conservation Fund please download and complete

the interactive application form. Applications for grants must be supported by a quotation from a recognised brass conservator and submitted to:

Martin Stuchfield

Hon. Conservation Officer

Pentlow Hall

Cavendish

Suffolk CO10 7SP

conservation@brasses.org

The Conservation Officer will be happy to discuss conservation requirements and requests for grant funding with incumbents or churchwardens before a formal application is made. He can also advise on other possible sources of grant funding.

Grant applications are submitted to the Executive Council for consideration at the next available meeting. Three such meetings are held each year, normally in February, May and October. The size of the grant awarded usually depends on three factors:

- the number of applications received;

- the total cost of conservation for each application; and

- the parish's own resources and other conservation work the parish is funding.

Grants will not be paid until the conservation work has been completed and must be taken up within two years of the award of the grant. However, if a parish cannot complete the work within the two years and the grant expires, the M.B.S. will consider an extension to the time limit.

Back to the topRight: detail from the monumental brass to Sir Thomas Bullen, K.G., Earl of Wiltshire and Ormond, 1538, from Hever, Kent. Photo: ©Martin Stuchfield

- © Monumental Brass Society (MBS) 2026

- Registered Charity No. 214336