Sir Hugh Hastyngs

- Date of Brass:

- 1347

- Place:

- Elsing

- County:

- Norfolk

- Country:

- Norfolk

- Number:

- M.S.I

- Style:

- London (Hastings)

Description

March 2005

March's brass of the month, one of the most magnificent ever produced, is in the parish church of Elsing, Norfolk, and commemorates its builder, Sir Hugh Hastyngs. He was the son (probably born in 1307) of John, 2nd Baron Hastings, by his second wife, Isabel, daughter of Hugh le Despenser, Earl of Winchester. He was an important royal commander under King Edward III in the early stages of the Hundred Years War, during which he saw much active service in France and Flanders, being present, among other battles, at Crécy (1346), where the young Black Prince first distinguished himself. He married Margery, daughter and heiress of Sir Jordan Foliot, through whom he acquired the manor of Elsing, and died in 1347.

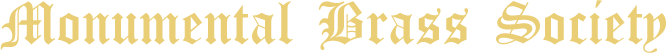

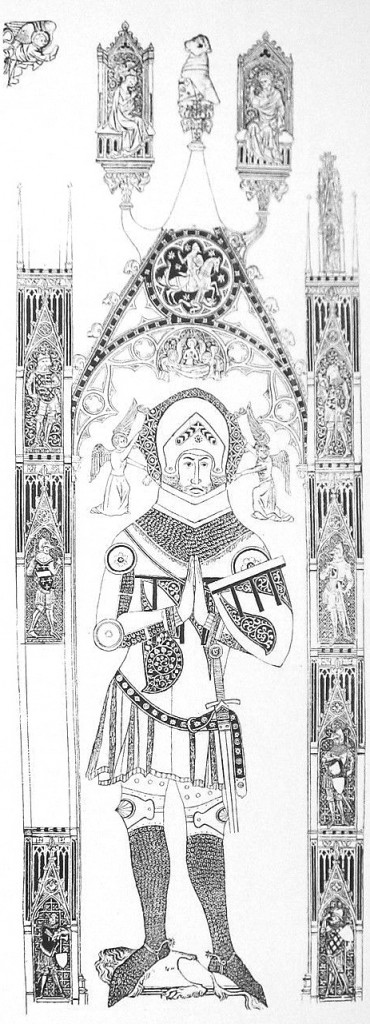

Sir Hugh is depicted, in imitation of a sculptured effigy of the period, as if recumbent, with his hands held together in prayer, and his head on a cushion supported by two angels. His legs are missing below the knees, but we know from an 18th-century impression of the brass made when it was more complete (shown opposite) that his feet rested on a crouching lion.

He is set within an elaborate gabled canopy which represents in metal the kind of stone canopy, either carved over the front of a wall-recess, or free standing, that covers many sculptured effigies. Each of the side-shafts was originally surmounted by a pinnacle and a tabernacle containing the figure of an angel, and comprised four oblong panels, of which two are now missing, each containing the figure of a "weeper" (mourner) standing under a gabled canopy set against narrow tracery lights.

Inside the top of the arch of the main canopy is a representation of Sir Hugh's naked soul being borne aloft in napkin by two angels, and above this, within the gable, an equestrian figure of St. George spearing a prostrate devil, within a cusped circular frame. The central pinnacle of the canopy is partly missing, but the helm, once bearing the Hastings bull's head crest that originally surmounted it, still survives in the correct position. It is flanked by two panels mounted on brackets, and together engraved with a representation of the Coronation of the Virgin, with Christ and Mary enthroned, she being crowned by an angel. At the top of the brass is one of originally two censing angels.

The whole was originally framed by a marginal fillet engraved with a memorial inscription in Latin, and incorporating figures of the Four Evangelists and the arms of Sir Hugh and his wife. We know about this from a description of the monument made in 1408 referred to later.

All the metal surfaces were originally gilt, and the heraldry was partly filled with coloured composition, and, on some of the weepers, coloured glass. The tracery of the main canopy was also filled with coloured glass, as were four small shields cut above the canopy into the Purbeck marble slab in which the brass is set. This use of coloured glass on a monumental brass appears to be unique.

Apart from its sumptuousness and high artistic quality, the monument is of considerable importance to students of medieval monuments and armour for a number of other reasons.

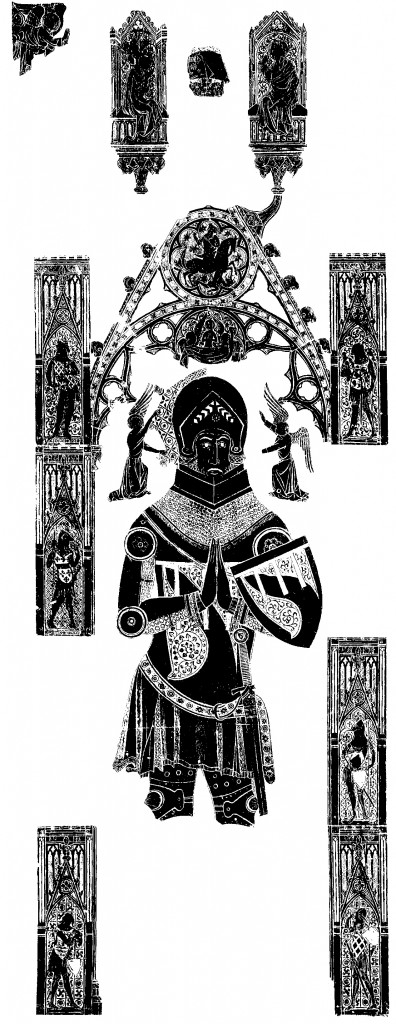

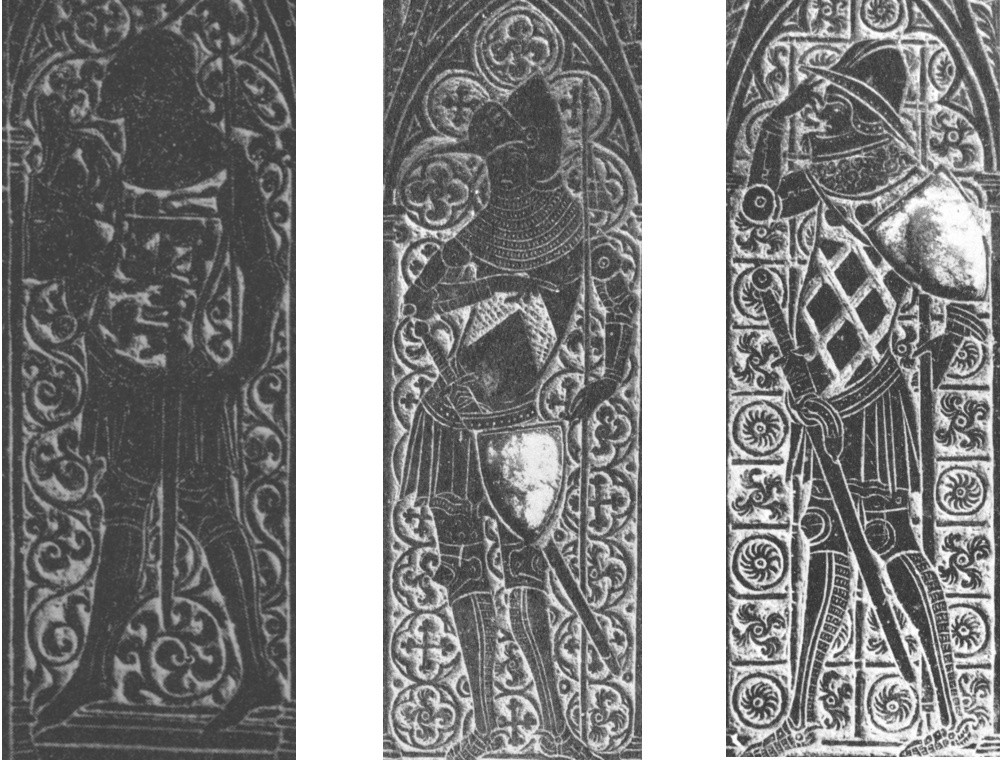

The weepers represented on medieval monuments are commonly members of the deceased person's family. Hastings, however, selected eight of his old comrades-in-arms from the French wars for this purpose, some of whom, though, were related to him. Two of the figures are missing, but their identities are known from the 1408 description of the brass, and in one case also from the 18th-century impression, both already mentioned.

The weepers are and were, in descending order from the top:

Right hand side of the main figure:

King Edward III

Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick;

Hugh le Despenser, Lord Despenser [missing];

Sir John Grey of Ruthin.

Left hand side of the main figure:

Henry, Earl of Lancaster;

Lawrence Hastings, Earl of Pembroke [missing];

Ralph de Stafford, Lord Stafford;

Almeric de St. Amand, Lord St. Amand.

Three of the figures, the Earls of Lancaster and Warwick, and Lord Stafford, each carries a lance with a pennon with a St. George's cross. Together with the King himself, they were founder members of the Order of the Garter, which was closely associated with St. George, who is, of course, prominently represented in the canopy of the brass (see left).

The earliest evidence for the use of the garter device dates from 1348, and the Order was not formally founded until the following year. There is, however, evidence to show that the King Edward had been considering the foundation of an order chivalry from at least as early as 1346. One may speculate, therefore, that the figures with St. George's pennons may have been members of a proto-order or association, which also included Hastings, and eventually became the Order of the Garter.

Together with the main figure and the figure of St. George at the top of the main canopy, the weepers provide illustrations - of particular importance because they are dated - of the type of armour in use during the fourth decade of the 14th century. This came at right at the end of a period of transition when the body-armour of mail (now incorrectly called "chain-mail"), that had been the norm since the early Middle Ages, was first reinforced with, and then largely replaced by, solid plates. Sir Hugh's own figure provides a very good example of this. His armour is basically mail - including the missing legs, which are shown on the 18th-century impression - but his arms are reinforced with large plates, his thighs are protected by defences made of small plates riveted to a textile or leather cover, as would also have been his torso under his heraldic coat-armour.

A uniquely important source of medieval arms and armour terminology is provided by a detailed description of the brass made in 1408 for the benefit of the Court of Chivalry in connection with a dispute over the right to a particular coat-of-arms between Reginald, Lord Grey of Ruthin and Sir Edward Hastyngs.

There have been suggestion that the brass was made in East Anglia, but the author considers that, in the absence of any evidence for the existence of a workshop producing brasses of any kind there - let alone ones of such high quality - in the mid-14th century, this cannot be taken seriously and that this brass is a London product.

© Claude Blair

Photo: © Martin Stuchfield

Rubbing: © The Monumental Brasses of Norfolk by William Lack, H. Martin Stuchfield and Philip Whittemore (forthcoming)

- © Monumental Brass Society (MBS) 2026

- Registered Charity No. 214336