John Browne

- Date of Brass:

- 1581

- Place:

- Halesworth

- County:

- Suffolk

- Country:

- Number:

- Style:

- London G (Daston)

Description

March 2012

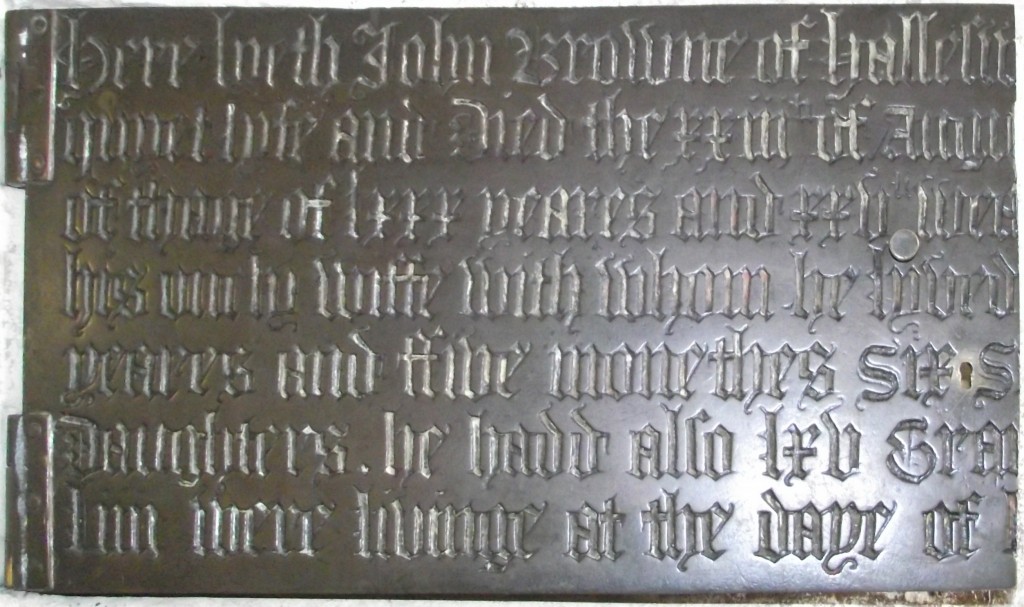

On 26 May the Society will visit Suffolk on an excursion. We will stop for lunch at Halesworth, a small market town, and examine the brasses there. One of these commemorates John Browne, who according to his inscription led a 'quiet life' before his death in 1581.

The history of his brass has been rather more eventful. According to the modern brass plate to which the original inscription is now joined by a hinge, in 1825 the remains of his brass were fished out of the River Waveney, which divides Suffolk from Norfolk, at a spot called the 'roaring arch' at the second bridge on Earsham Dam. Earsham is on the north side of the Waveney, in Norfolk.

The remains of John Browne's brass are now set in a new stone above the original indent. Quite how and when the brasses came to be put in the river, some dozen miles north of Halesworth, is not known. The church was visited by the iconoclast William Dowsing on 5 April 1644, when he recorded five 'popish' inscriptions of brass, but the Browne brass would not have given offence and it should have been left alone. (Indeed the remaining brasses to John Everard, 1476, and William Fiske, 1512, should have been 'cleansed', but the inscriptions survive intact. Either Dowsing was not thorough, or his instructions to deal with offending inscriptions were not followed.)

We have no further details of how the brass pieces were recovered from the Waveney. It seems likely that they were in some sort of bag or container, so as to be recovered together. This suggests that they had not been in the river very long, and that they had been stolen by thieves. Nor is it clear how the pieces were identified as from Halesworth. Perhaps it was common knowledge locally that the church had been raided.

John Browne is recorded as holding two messuages, two yards and a meadow called 'Le Hope' in Halesworth in 1557, and he probably held other land outside the town. He also held the advowson of Ubbeston in 1556. His son John, who survived him by only ten years, was lord of the manor of Spexhall, about two miles north.

John junior and his wife, Silvester, also had a brass to their memory, at Spexhall. This has had a slightly less chequered history. It was in place in 1808, but by the mid nineteenth century was recorded as missing. In fact it was in the rectory, and was still there in 1903, although it is back in the church today. Today the figure of Silvester, her six sons and separate inscriptions to John and Silvester remain, but are reset. The figure of John junior, like that of his father, is completely lost.

A comparison of the brasses to father and son is instructive. The inscription at Halesworth is now incomplete, but originally read:

Here lyeth John Browne of Hallesw[orth, who lyved a

quiet lyfe, and died the xxiiih of Augu[st in the yeare 1581

of the age of lxxx yeares and xxv wea[kes, he hadd bye

his onely wiffe, with whom he lyved [fifty four

yeares and ffive monethes, Six S[ons and ten

Daughters. He hadd also lxv Gra[ndchildren, of whom

liiii were livinge at the daye of [his decease.

It is curious that this inscription does not give the wife's name.

John junior's inscription at Spexhall is in Latin but gives its details in a very similar way. He died on 17 August 1591, aged 45, having been married for 25 years and leaving six sons and five daughters. There is then a separate inscription for Silvester, also in Latin, telling us she died on 7 May 1593 aged 47. It may be that the details of John senior's wife were also given on a separate plate. There is an indent between John senior's inscription and the two groups of children. This indent is long and narrow, but suitable for a very short single-line inscription.

Enough remains of John senior's brass at Halesworth to indicate that it belongs to those brasses that John Page-Phillips identified as the 'Daston' style. I regard 'Daston' more loosely, as a group of similar brasses within which two or three different styles can be distinguished, with that exemplified by this particular brass as the most distinctive. All these brasses are believed to have been designed if not engraved in Southwark, across the Thames from London.

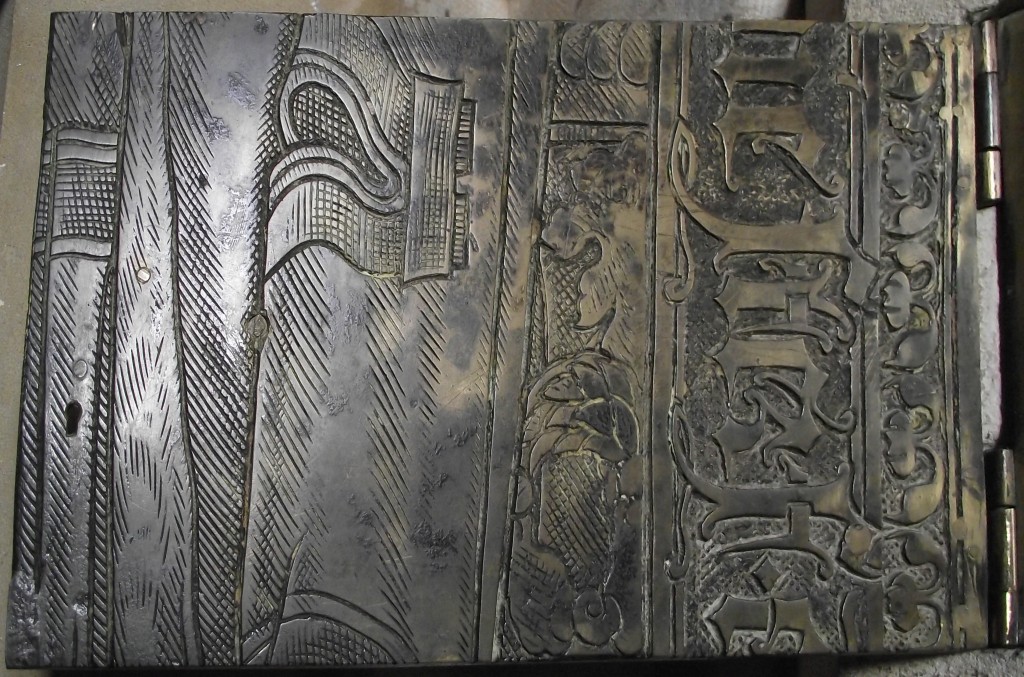

The reuse of old brass plates was rife at this time, with the source of the plate generally being the Low Countries, where churches were being looted in the name of religion. The inscription ofJohn senior's brass is one such piece, having on its reverse part of a marginal inscription in Dutch or Flemish and the edge of the hanging sleeve of a man in civilian clothing. Another piece of the same brass can be found behind part of a shield at Great Berkhampsted in Hertfordshire. Intriguingly, the plate with the ten daughters, of which only the upper part survives, looks like it should be palimpsest, although it is not recorded as such.

The modern brass to which the old inscription is joined records the complete wording of the old inscription, and also the circumstances of its return to the church. This took place in or before 1868, when the Ipswich Journal carried a long report on the re-opening of Halesworth church after the addition of a new aisle. It describes, with a few minor inaccuracies, the Browne brass and the modern plate. The Rev Samuel Blois Turner, elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1843 while he was perpetual curate at Great Linstead, Suffolk, had at some point acquired the pieces retrieved from the river. It seems unlikely that this was in 1825, the year after he had entered Pembroke College, Cambridge at the age of eighteen. He was ordained deacon at Norwich in 1829 and priest the following year. In 1832 he was appointed perpetual curate at Little Linstead, a few miles west of Halesworth, then at Great Linstead in 1838, before becoming rector of nearby South Elmham in 1861. His second wife, Marian, whom he married in 1852, was the daughter of Rev Robert Hankinson, rector of Halesworth. During the work on the church, the indent of the Browne brass was recovered and Blois Turner instantly recognised it as such. The brass fragments and the original slab are now reunited, although the brass plates are now set into a different piece of stone.

Copyright: Jon Bayliss

- © Monumental Brass Society (MBS) 2026

- Registered Charity No. 214336