Andrew & Elizabeth Jonis

- Date of Brass:

- 1497

- Place:

- Hereford Cathedral

- County:

- Herefordshire

- Country:

- Number:

- Style:

- Burton-upon-Trent

Description

November 2023

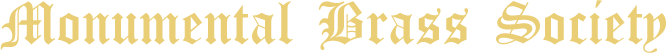

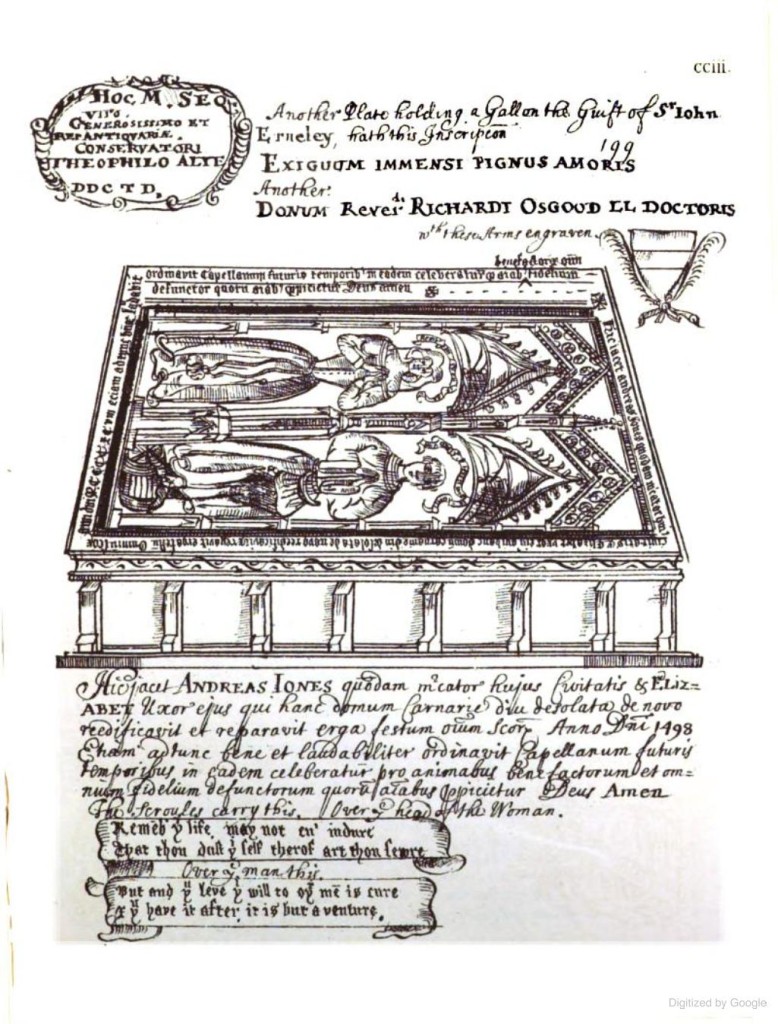

The crypt below the Lady Chapel in Hereford Cathedral contains a late fifteenth-century alabaster incised slab commemorating Andrew Jonis, a Hereford merchant, and his wife Elizabeth. It was in place, as its inscription tells us, by or soon after the feast of All Saints (November 1st) 1497. It forms the top slab of a low tomb chest, today rather plainer than when Thomas Dingley drew the whole monument during Charles II’s reign for his History from Marble.

In 2004 our member Sally Badham published a short article on this slab in the Society’s Transactions. As she noted, the slab is in fine condition, albeit with some cracks in its lower part. Dingley’s drawing is not entirely accurate in its treatment of the double canopy and of the figures of Andrew and Elizabeth, but includes his transcription of the marginal inscription. Sally Badham’s version expands the contractions: Hic jacet Andreas Jonis quo(n)dam m(er)cator hui(us) civitatis et Elizabet uxor eius qui hanc domu(m) carnarie diu desolata(m) de nouo re edificauit et rep(ar)auit erga festu(m) om(nium) s(an)c(t)or(um) anno d(omi)ni MCCCC xcvij. Eciam ad tu(n)c b(e)n(e) et laudabilit(er) ordinauit capellanum futuris temporibus in eade(m) celebratur(um) p(ro) a(n)i(m)ab(us) benefactor(um) et om(nium) fidelium defu(n)ctor(um) quor(um) a(n)i(m)ab(us) propicietur deus amen. (Here lies Andrew Jonis, once merchant of this city, and his wife Elizabeth; he rebuilt and repaved this charnel house which had long been derelict, in time for the feast of All Saints 1497; he also then well and laudably instituted a chaplain to celebrate in ages to come therein for the souls of the benefactors and of all the faithful departed, on whose souls may God have mercy. Amen.)

Sally also expanded the contractions in Dingley's transcription of the English text of the scrolls:

Reme(m)b(er) thy life may not eu(er) i(n)dure That thow dost þiself therof art þu sewre

But and þu leve þi wil to oth(er) me(n)is cure A(n) þu have it aft(er) it is but a ve(n)tur.

Note the use of the old letter þ (thorn) that persisted through the Middle Ages before being replaced by th or y.

Sally drew attention to similarities between these figures and those on the slab of 1473 for Richard and Matilda Greneway at Stretton Sugwas, not far outside Hereford. Despite a gap of nearly twenty-five years between the two slabs, the simplicity of the incised lines used to depict the figures on both slabs suggests a continuity of design. Later slabs in Herefordshire at Turnastone and Aymestrey, both with dates of death in 1522, are less appealing.

All these slabs are the products of workshops at Burton-upon-Trent in Staffordshire. Early sixteenth-century Burton work is generally more rigid and standardised in its approach than that of the latter part of the previous century. The Jonis slab is more complex than that at Stretton Sugwas, with a more complex canopy and scrolls coming from the mouths of Andrew and Elizabeth. Consequently the engraver has wisely dispensed with the cushions that are behind the heads at Stretton Sugwas. Andrew’s hair is as short as that of Richard Greneway and, on a slab in St Mary’s Shrewsbury, of Nicholas Stafford esquire, died 1473. At a time when men’s hair was becoming longer, was Andrew Jonis deliberately harking back to the 1470s?

The Latin marginal inscription tells us that he rebuilt and repaved the long-derelict charnel house (in which his tomb stands) and that he put a chaplain in place to pray not only for himself and Elizabeth but for all the faithful departed. Charnel houses were where the bones of the dead were stored after the burial of new bodies in churchyards had disturbed old bones. Thomas Farrow’s research into charnel houses has established that Andrew Jonis’s choice of burial place was by no means unprecedented. However his monument is one of only two erected by choice in a charnel chapel that survive to this day. All trace of the skulls and long bones that can still be found in other charnel houses such as Rothwell has disappeared from Hereford.

Incised alabaster slabs are particularly prone to wear when used as floor slabs, so the survival in excellent condition of this slab is to be celebrated. Too often, alabaster floor slabs are so worn as to be barely identifiable, or are unevenly worn, part of the slab being worn away by the passage of feet while another part survives in relatively good condition. Such slabs were also cut up to fit in with reflooring or, in a few cases, to make new alabaster articles such as pulpits.

Copyright: Jon Bayliss

References

T. Dingley, History from Marble compiled in the Reign of Charles II, ed. J.G. Nichols, Part 1, Camden Society, 94 (London, 1867), p. cciii.

TMBS 17 part 2 (2004), 176-7, 179.

- © Monumental Brass Society (MBS) 2026

- Registered Charity No. 214336